A new class of migraine preventive medication is on the way, and whilst you should be excited about its possibilities, it is accompanied by a lot of hype, some positive results, some misleading claims, and a hefty price-tag. Now more than ever you need to understand the facts about these drugs so you can inform yourself about their appropriateness for you.

Anyone keeping an eye on ‘migraine news’ over the last 12 months will have found it hard to miss reports of a new class of ‘wonder drugs’ for migraine prevention. The CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

A client of mine last year sent me a news video quipping ‘this will put you out of business’. Honestly, I would love nothing more that to wake up one day and find that someone has ‘cured’ headaches and migraines forever.

Some experts in the field such as lead researcher in CGRP inhibitors, David Dodick, are describing this new class of drugs as ‘the most exciting thing we’ve seen’ in over 20 years of his practice1 .

On the other hand specialists such as Robert Cowan at a meeting of the Headache Cooperative of New England in 2017 in Boston asked:

“Why is it that a new class of drugs that appears to be marginally (if that) more efficacious than currently available medications has caused such a stir?2 ”

With seemingly conflicting opinions from experts in the neurological community, my primary goal in attending the American Headache Societies Annual scientific meeting in San Francisco in June was to find out, directly from those involved, the facts about these drugs and why they are so excited about seemingly ‘okay’ results. I’m glad to say I now understand.

I will explain what CGRP is, what the research says, why there is excitement around the antibodies and what can we realistically expect when they arrive in Australia.

What is CGRP?

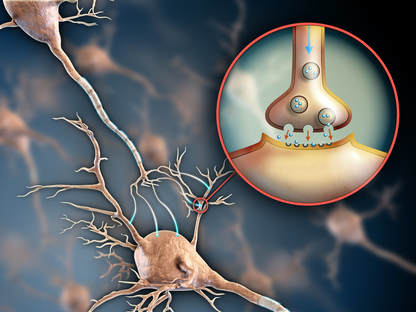

CGRP or Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide is a protein produced by certain nerve cells in the body. Performing different functions in different areas it forms part of the inflammation/healing pathway. In the spinal cord it plays a role in regeneration of nervous tissue after injury, and it is also vasoactive, dilating blood vessels that maintain blood flow to the heart and brain and plays a role in fracture healing. In the stomach it appears to play a role in regulation of gastric secretion and gastrointestinal hormone release.

After stroke it can help to limit swelling (oedema) in the brain, to such an extent that it is an area of interest (administering it, not destroying it) as an acute treatment for stroke victims3 .

Specifically for migraine the cell bodies on the trigeminal ganglion are the main source of CGRP. It acts as a pro-inflammatory mediator (along with dopamine and 5-HT), released when the trigeminal nerve is over stimulated or irritated, to excite nociceptive (pain) pathways.

It has been widely understood for decades now4 that overactivity of the trigemino-cervical nucleus is common to all major headache types, and in 1990 researchers taking blood from migraineurs found elevated levels of CGRP5 . In line with the reflex and imaging studies, interictal (in between episodes) CGRP levels are found to be elevated.

This started researchers investigating into where CGRP was released and whether changing it would help. What they found was they were already targeting it, they just didn’t know it. The Triptans help the body absorb serotonin, which binds to excitatory trigeminal ganglion neurons and blocks their action – decreasing excitability, by blocking release of CGRP.

The hypothesis was then:

“If CGRP is present all the time, maybe elevated levels are the cause of, rather than product of migraine”.

You can imagine the excitement!

Unfortunately trials injecting CGRP into the bloodstream of non-migraine sufferers compared to sufferers did not yield the results that indicate it as a causative agent. CGRP induced migraine attacks in migraine sufferers, but does not cause migraines in non sufferers6 . Despite this result the rather misleading conclusion was drawn that CGRP may be causative in migraine7 . If it was, it would also cause migraine in non-sufferers.

Again……..CGRP does not cause migraines infused into the bloodstream of non-sufferers. You need to be a migraine sufferer already for elevated CGRP to trigger an attack.

What are CGRP monoclonal antibodies?

What has been developed is a monoclonal antibody – that is an antibody that is very specific to CGRP, and doesn’t have an immune response – but circulates in the blood stream waiting for CGRP to be released and binds to it for removal from the body.

So the trigeminal system is still overexcited, releasing CGRP, but these antibodies wait for it and bind to, and eliminate it.

It is truly amazing, and if elevated CGRP was the only issue then it would be as good as a cure.

So what are the results?

Erenumab (brand name – Aimovig), was the first of the new class of medications approved by the American FDA in May 2018.

Across a number of trials8 9 10 , with the primary outcome measure being a 50% reduction in number of migraine days per month, erenumab achieves between 30 and 40%. That is that 30-40% of people on the active medication achieved a 50% or greater reduction in migraine days per month. When you compare it to placebo we see between 15% and 30% achieving the same reduction.

What this means is that the risk reduction or ‘real’ effect over placebo is somewhere between 15-20%.

This is a good rather than great result, and has implications when we factor in cost to the healthcare system as Forbes magazine columnist Joshua Cohen points out11 .

“Every 6th patient taking erenumab will benefit from this medication. A number needed to treat of 6 is not a great result. In fact, it is worse than the current standard of care – triptans. For high-dose triptans the numbers needed to treat are between 2.6 and 5.1. Adopting a conventional trial-and-error method to prescribing means that doctors would need to prescribe to 6 patients before one would get benefit from erenumab. Unfortunately, there is currently no way of knowing which patient will be the lucky one.”

The current list price in the US for Aimovig is $575 per month or $6900 per year (USD). For the one person in 6 who gets the result this may be seen to be a cost effective solution, however for the other 5 sufferers it clearly is not.

By comparison trials have shown similar 50% responder rates with far cheaper and widely available supplements:

There is variability amongst these trials with the trial quality and profile of subjects, so there does need to be a degree of caution with comparing a single number across trials.

Having said that all these trials were presented recently in San Francisco and the results are not insignificant, and given the significant cost involved with the new class of drugs, it’s a reasonable question to ask – are the mildly better results and potential serious side effects are worth it?

In part 2 – Side effects, after-release concerns and what to expect when these drugs arrive in Australia.