This isn’t yet another blog (a seemingly endless procession of the same content) telling you what you already know……..about a severe headache affecting one side of the head lasting 4-72 hours, associated with nausea/ vomiting and a sensitivity to light or sound. If you are new to the migraine space and don’t ‘already know’ how a migraine is classified you can read about it here.

You deserve better than an ‘auto-blog’ feed of a cut-shuffle-paste of everything that has been written about migraine for the past couple of decades.

I’m going to take you on a little journey from what we accept as the standard definition of migraine, and why that came to be.……..and challenge you to understand that at the heart of the disorder is a sensitive brainstem, overstimulated by sensory input from multiple channels (the most potent and constant of which is the upper cervical spine), and that the symptomatic output of this can often manifest itself as a strong one sided unilateral headache with nausea and sensitivity to light, but can also manifest itself as a pure headache (tension-type headache), headache with neck pain (cervicogenic headache), a vestibular disorder, a gastrointestinal disorder………and maybe much more.

Why is migraine defined as a headache?

The condition that we now known as migraine was first described by Hippocrates in 400B.C. :

“flashes like lightning seemed to dart from his eye, and generally his right eye. Not long after, a violent pain seized his right temple, and then his whole head and neck. The back part of his head at the vertebrae swelled; and the tendons were upon the stretch and hard”

Headaches were a common problem even in antiquity, but the unique associated features including gastrointestinal disturbance, aversion to sensory stimulus (light, sound odours), and most spectacularly, the visual phenomena associated with migraine aura, distinguished migraine from other forms of headache.

Several centuries later the Roman physician Galen coined the term ‘hemikrania’ – derived from ‘hemi’ meaning half and ‘kranos’ meaning head – to describe the same condition. Through several millennia of being used and passed on through traditional verbal means, and via translations across cultures and languages Galen’s ‘hemikrania’ has appeared as ‘megrim’, ‘emigranea’, ‘magrym’, ‘bilious headache’ and ‘sick headache’ amongst others. The French derivation has now become universally accepted as the standard form – migraine.

Through that time one sided headache has remained the constant, with other symptoms coming in and out of favour – at times the emphasis was on nausea and vomiting and at other times the sensitivity to light, sound and smell were more pronounced. Unbeknownst to them, the problem that early authors (healers and medical practitioners) were confronted with was that migraine (or the underlying disorder/s that cause it) is a heterogeneous disorder. As we a dealing with the nervous system we all have slightly different pathways develop with different thresholds, leading to a vast differences in tastes, preferences and abilities. Given that healthy expression of individual nervous systems produces a range of results, it follows that a dysfunctional expression of an individuals nervous system will also produce a range of results – migraine has many different faces, and two may be similar, but rarely the same.

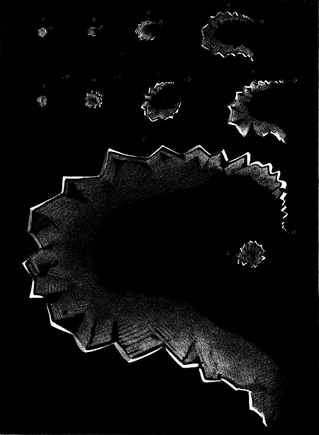

One of the most obvious and significant ‘shifts’ in defining migraine occurred in the late 19th century when astrologist Hubert Airy published sketches of his migraine aura.

Up until this time the only way physicians could ‘see’ a migraine was the debilitating impact it would have on the sufferer, but it was difficult for the doctors with the the knowledge they had at the time to differentiate migraine from forms of transient mania, psychosis or mental illnesses.

When Airy, a respected scientist, produced his artwork two things happened. On the one hand legitimised migraine, but at the same time, marginalised anyone who wasn’t affected by an aura.

Aura became synonymous with, and for many doctors, diagnostic of, migraine (a common misconception that still exists today – many patients will say they don’t think they have migraines because they don’t get auras). The term ‘classic migraine’ came to be associated with migraine with aura (migraine without aura was relegated to ‘common migraine’) and for a time, migraine aura was considered the ‘fingerprint’ of the migraine condition.

Classification of headache disorders

At the heart of any legitimate scientific pursuit is a description of the object of study. In the late 1950’s a group of eminent neurologists formed an Ad Hoc committee to propose definitions for each different headache type, so as moving forward into research we have standardised descriptions of what does, and does not constitute a migraine in order to compare ‘apples with apples’ as it were. This eventually led to the formal classification of headache disorders which is now up to version 3 (2018) with the fourth version in progress.

At the heart of any legitimate scientific pursuit is a description of the object of study. In the late 1950’s a group of eminent neurologists formed an Ad Hoc committee to propose definitions for each different headache type, so as moving forward into research we have standardised descriptions of what does, and does not constitute a migraine in order to compare ‘apples with apples’ as it were. This eventually led to the formal classification of headache disorders which is now up to version 3 (2018) with the fourth version in progress.

There is a whole other (and probably multiple) blog on whether the classification criteria are valid, and look at all the diagnostic gaps many people fall into that lie between somewhere between a migraine and tension-type headache………but no. The aim of this little piece is to broaden your thinking about what a migraine represents……..and potentially how many people may have their own version of a ‘migraine’.

Migraine or not migraine?……..that is the question.

Prior to Hubert Airy was depicting his migraine, two other eminent scientists English, an eye specialist David Brewster, and Sir John Herschel (renowned mathematician, astronomer, chemist) noted visual phenomena that we would now recognise as migraine aura without headache or ‘silent migraine’. These are transient visual disturbances that are not accompanied by headache, and often no other ‘associated symptoms’ (nausea, sensitivity to light/sound).

This poses a dilemma for the nosology or ‘naming’ of migraine. There is no headache here, one sided or otherwise (keeping in mind that almost half migraine headaches are bilateral). However aura has now become synonymous with migraine, so surely it is the same thing? The fact the Airy amongst others who suffered migraine with aura, would also frequently have the aura without a progressing to a headache was the bridge that joined to the two conditions – but now we have an interesting proposition. Is a migraine still a migraine if it appears as just one symptom (i.e. aura) without the others?

A case in point here is a one sided featureless headache – despite it affecting ‘half the head’ we would call that a tension-type headache.

Another case (far too close to my own heart………or head) is vestibular migraine or VM.

VM is a condition of spontaneous or induced, dizziness or vertigo with at least 50% of episodes accompanied by one ‘migrainous feature’.

Whilst the migrainous feature can include headache, it is not requisite, and can also just be photophobia (sensitivity to light), or visual aura. So if you had attacks of spontaneous vertigo of which 50% were accompanied by sensitivity to light,

Similarly, those with cyclic vomiting syndrome, or chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome have periodic episodes, often with the same types of triggers as migraineurs, and rarely do they have headache.

What about Irlen syndrome – defined as a perceptual processing disorder, it is a chronic photophobia. Is this a form of migraine that only presents with one symptom?

I have no doubt that in many cases these are different version of the same problem. Essentially all the byproduct of an overstimulated brainstem that is now operating in ‘crisis mode’ – this is why anything that increases your mental or physical stress (i.e. a potential threat) will potentially become a trigger.

My question is how far does this go? Some of the most common features of migraine (that don’t make it into the official classification) such as:

Lethargy

Lethargy- Brain Fog

- Sleep dysfunction

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Poor memory

- Gastrointestinal issues

Now of course before I’m accused of quackery, I’m not for a moment saying that everyone with depression or a sleep disorder, or brain fog actually have migraine.

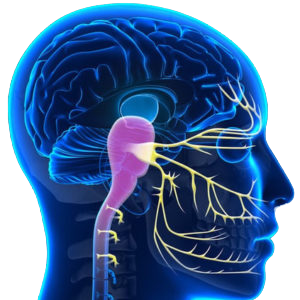

What I am saying though, is this. We know from the imaging studies that hyperactivity in key areas of the brain underpin migraine. You can almost make a ‘brainstem recipe’ for areas that you will activate to produce certain symptoms.

We all develop differently via a combination of genetics (predetermined biases in pathways) and everything that happens to us – this all shapes a unique neural network, that will have biases and preferences – picture a river running through your brainstem that might be similar, but never the same as someone else’s. The names here are not important – just that there are different brainstem regions that we can isolate and account for different symptoms.

We all develop differently via a combination of genetics (predetermined biases in pathways) and everything that happens to us – this all shapes a unique neural network, that will have biases and preferences – picture a river running through your brainstem that might be similar, but never the same as someone else’s. The names here are not important – just that there are different brainstem regions that we can isolate and account for different symptoms.

Headache: this is undeniably a symptoms of the trigemino-cervical complex or TCC. This is the part of brainstem that receives direct input from the nerves of the head and face (trigeminal) and upper cervical spine.

If activated in isolation the result would look like tension-type headache or cervicogenic headache.

Nausea: the part of the brainstem responsible for controlling the threshold of nausea is the solitary nucleus or NTS. Interestingly the NTS receives direct input from the upper cervical spine to help control blood pressure when we change posture.

If this is activated in conjunction with the TCC above it would look like migraine. If activated in isolation we would see cyclic vomiting syndrome or chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome.

Dizziness/vertigo: Undeniably the vestibular nucleus is the master controller of such symptoms, but this is an integrative nucleus, receiving strong input from the small upper neck muscles (which have the power to suppress inner ear activity), and the visual system.

If activated in concert with the TCC and NTS we would see something like a vestibular migraine. If activated in isolation would it look like Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness or PPPD?

Brain fog, lethargy, memory problems, sleep disturbance+/- aura:

Okay that’s a broad swipe, and it’s important to remember that many other part of the brain (i.e. hypothalamus) also have roles here, but the Locus Coeruleus or LC located in the middle of the brainstem – the pons, is an underrated ‘master controller’ with dysfunction known to cause cognitive decline, memory problems, lethargy and sleep disturbance.

Our main threat response system starts in the brainstem, with the Locus Coeruleus acting as a gatekeeper to the amygdala (fear and threat centre) and general brain excitability.

Aberrant activity in the Locus Coeruleus causes decreased cognitive function globally and has been implicated as a generator for cortical spreading depression in mice – this is the physiological substrate of migraine aura. Increased activity of the LC will create anxiety-like symptoms, and is implicated in chronic anxiety disorders.

The LC also controls the volume (modulates the gain) of the vestibular nucleus. What makes you more alert, and more anxious than losing your balance? Very little.

How many vestibular disorders (PPPD and Vestibular migraine included) are triggered by, and often diagnosed/treated as anxiety disorders?

The LC is very sensitive to pain inputs (threat response) and especially when they are one sided. We see a one sided problem in the neck, that connects directly to the TCC, NTS, and vestibular nucleus. What we see clinically is that not only can treating the upper cervical afferents change headache (via TCC), but also impacts on nausea and vomiting disorders, vestibular disorders, and concurrently impacts on patients sleep and mood.

Is it possible, and even probable then that you could have a migraine that just affects one area?

What does your migraine look like? Chances are if you are reading this it’s because you have some quite classic symptoms – but you will have friends who will have periods where they are sharp, engaged and focussed, and then seemingly inexplicably they ‘zone out’, are lethargic.

Using the Watson Headache ® Approach we can determine if you have this same small fault affecting the top of the neck in the initial assessment. We only progress to treatment if this fault is identified. Treatment is drug-free, safe, and it is most commonly corrected and able to be self managed within a few weeks. It might just change your life!

Using the Watson Headache ® Approach we can determine if you have this same small fault affecting the top of the neck in the initial assessment. We only progress to treatment if this fault is identified. Treatment is drug-free, safe, and it is most commonly corrected and able to be self managed within a few weeks. It might just change your life!